The History of Plymouth Meeting Friends

Colonial Quakers

Quaker missionaries arrived in North America in the mid-1650s. The first was Elizabeth Harris, who visited Virginia and Maryland. By the early 1660s, more than 50 other Quakers had followed Harris.

However, as they moved throughout the colonies, they continued to face persecution in certain places, particularly in Puritan-dominated Massachusetts, where several Quakers - later known as the Boston Martyrs - were executed during the 1650s and 1660s.

William Penn

In 1681, King Charles II gave William Penn, a wealthy English Quaker, a large land grant in America to pay off a debt owed to his family. Penn, who had been jailed multiple times for his Quaker beliefs, went on to found Pennsylvania as a sanctuary for religious freedom and tolerance.

Within just a few years, several thousand Friends had moved to Pennsylvania from Britain. Quakers were heavily involved in Pennsylvania’s new government and held positions of power in the first half of the 18th century, before deciding their political participation was forcing them to compromise some of their beliefs, including pacifism.

Plymouth Meeting Settlement

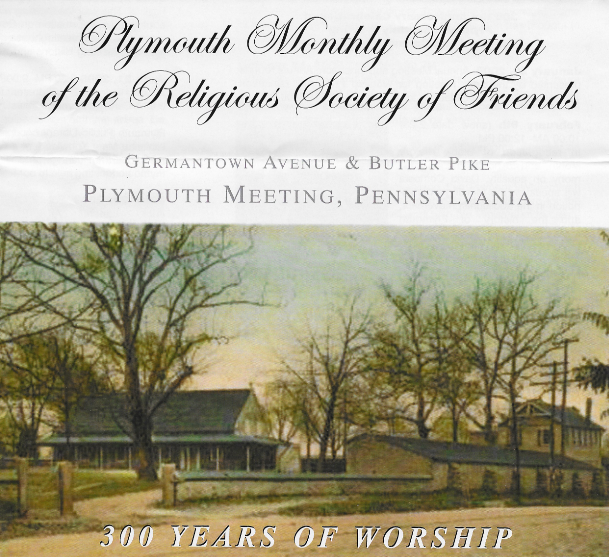

The area that is now Plymouth Meeting, Pennsylvania was originally settled by members of the Religious Society of Friends, or Quakers, who built the Plymouth Friends Meetinghouse in 1708. They had sailed from Devonshire, England, on the ship Desire, arriving in Philadelphia on June 23, 1686. The settlement takes its name from the founders' hometown of Plymouth in Devonshire.

As described in History of Montgomery County (1858), the village of Plymouth Meeting was:

"...situated at the intersection of the Plymouth and Perkiomen turnpikes, on the township line. On this [Plymouth] side is the meeting house, school house and four houses; and in Whitemarsh two stores, a blacksmith and wheelwright shop, post office and twenty-four houses. The houses in this village are chiefly situated along the Perkiomen or Reading pike, nearly adjoining one another, and being of stone, neatly white washed, with shady yards in front, present to the stranger an agreeable appearance."

The Welsh settlers of Plymouth were members of Radnor, Marion and Haverford Meetings before they built a meetinghouse of their own. When their new Plymouth Meetinghouse was ready, Radnor Friends wrote a letter asking members of Plymouth "please do not forget us."

Plymouth History Timeline click here

Roads Connecting to Plymouth Meeting

What is now Germantown Pike was ordered laid out by the Provincial Government in 1687 as a "cart road" from Philadelphia to Plymouth Meeting. The actual road was finished in 1804, at a cost of $11,287.

A road from Plymouth Meeting to nearby Gwynedd Meeting appears to have been built in 1751.

What is now Chemical Road, following Plymouth Creek, was opened in 1759 to provide access to a new gristmill.

Revolutionary War Times

During the Revolutionary War, in May 1778, the Plymouth Friends Meetinghouse served as a temporary military hospital for the wounded from the battle of Germantown.

General George Washington, then at Valley Forge, learned that a British force intended to seize the area and cut off movement of the Continental Army. He sent the Marquis de Lafayette and 2,100 troops to counter. They camped around the meetinghouse on the night before the May 19 Battle of Barren Hill. The next morning the British arrived with a massive force of 16,000, and tried to cut off any escape route. The British army paused at the crossroad of Plymouth Meeting seeking to understand the lay of the land. Lafayette took advantage of the Americans' knowledge of local roads, and escaped with minimal casualties.

Abolitionist Engagement

Slave holding was condemned by the Society of Friends in 1754. Few slaves were held in Plymouth Township, and only one remained by 1830. Plymouth Meeting participated in the abolitionist movement and was a hub of activity during the Underground Railroad. Lucretia Mott lectured across the street from the Meetinghouse at Abolition Hall and is known to have attended the meeting.

The Maulsby and Corson families were early abolitionists, sheltering runaway slaves beginning in the 1810s and turning their properties into stations on the Underground Railroad.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 increased the penalties for giving assistance to an escaped slave to six months in prison and a $1,000 fine. It allowed slave catchers to pursue a fugitive across state lines into every U.S. state and territory. Local resident George Corson was involved in hiding Jane Johnson, whose 1855 escape exposed a loophole in the federal law.

When the doors to local churches and schools were closed to Abolitionist speakers, Corson built Abolition Hall (1856) on his farm at Germantown and Butler Pikes. The hall, a short walk from Plymouth Meetinghouse, could accommodate up to 200 people, and hosted speakers such as Frederick Douglass, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Lucretia Mott, Mrs. Stephen Foster and William Lloyd Garrison.

McCarthy Era

During the McCarthy Era the Committee staged an investigation of Mary Knowles, librarian of the Plymouth Public Library that occupied a building on the Meeting property. Mary Knowles was accused of being a communist. Plymouth Meeting responded in her support, based on their testimony of Integrity, with repercussions to the meeting.